For those that missed it, by popular demand here is the complete article published in World of Interiors October 2016 edition.

The article records the discovery, acquisition and reflections upon the Chrystiane Charles’ collection of drawings, photographs, sculptures and ephemera.

© The Condé Nast Publications

Text: Timothy Brittain-Catlin. Photography: Tim Beddow

The artist and dealer Peter Woodward knew

that the sale was going to be amazing, but he had no idea what

a revelation it actually would be. He had already opened his

stand at the Battersea Decorative Antiques and Textiles Fair

last October when he spotted an advertisement in La Gazette

Drouot, where French dealers read about upcoming auctions.

The very next day there was to be a viewing prior to a sale in

Paris, a vente judiciaire organised by the state to dispose of

assets for death duties, comprising the contents of Galerie

Chrystiane Charles. He dropped everything — his sister rush-

ing over to look after his pitch – and took the Eurostar. And

what he found when he arrived was breathtaking.

Peter knew Chrystiane Charles as an important designer

of lamps and furniture; she had married into the Maison

Charles family of craftsmen in the 1960s and played an in-

creasing role in the company until her retirement 20 years

later. Over time he had collected and sold examples of her

work, mostly her lamps based on flower or fruit forms –

numbered bespoke models that never seemed to go out of

fashion. After leaving the firm, Chrystiane opened a gallery

on the rue Bonaparte – where Eileen Gray had lived for 70

years — and this was the collection that was now for sale. The

catalogue listed a vast quantity of covetable items but, as

Peter was among the first to arrive for the viewing at the Hotel

Drouot, he could also peer into a further 50 cases that had

been added to the sale at the last moment. In these were

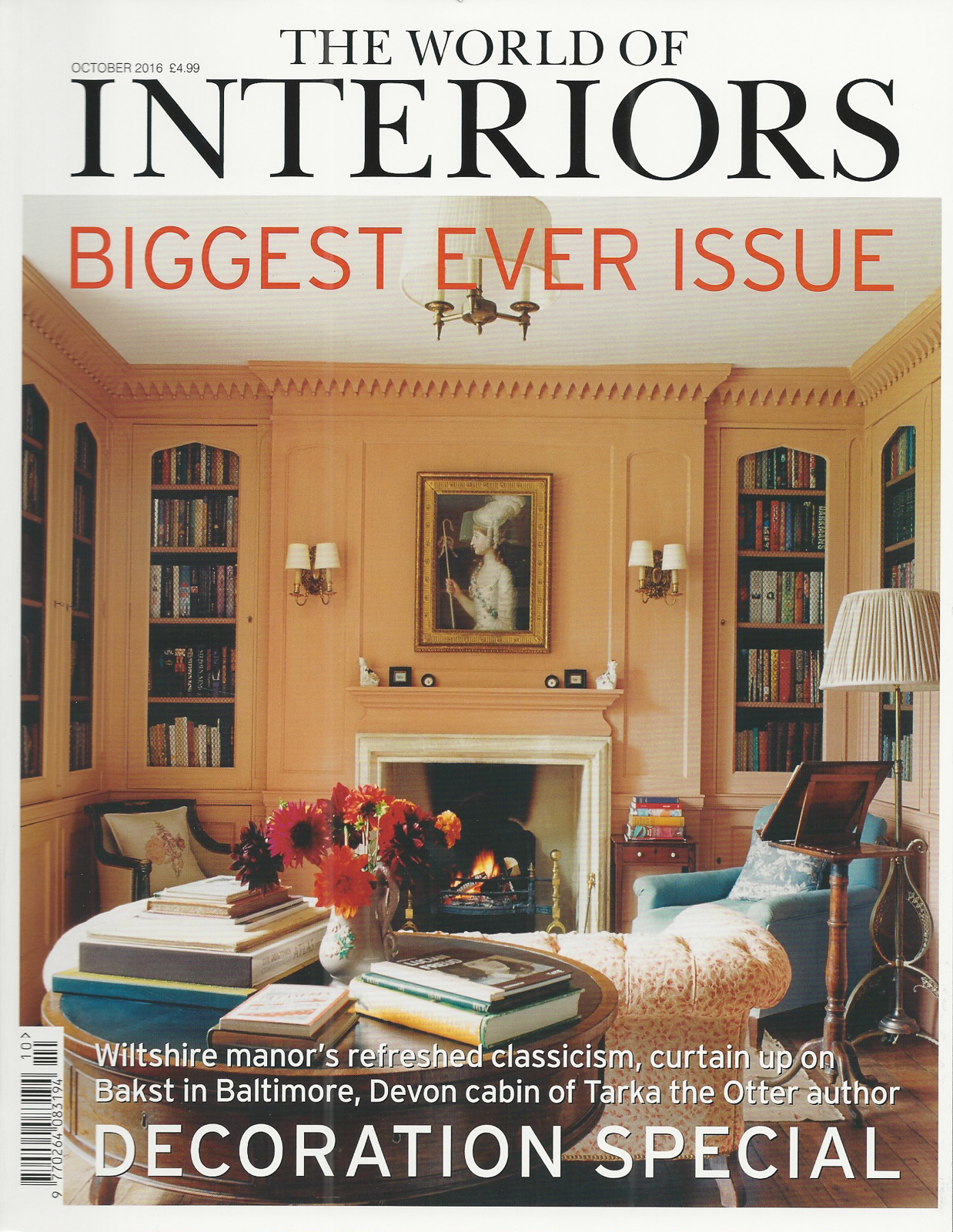

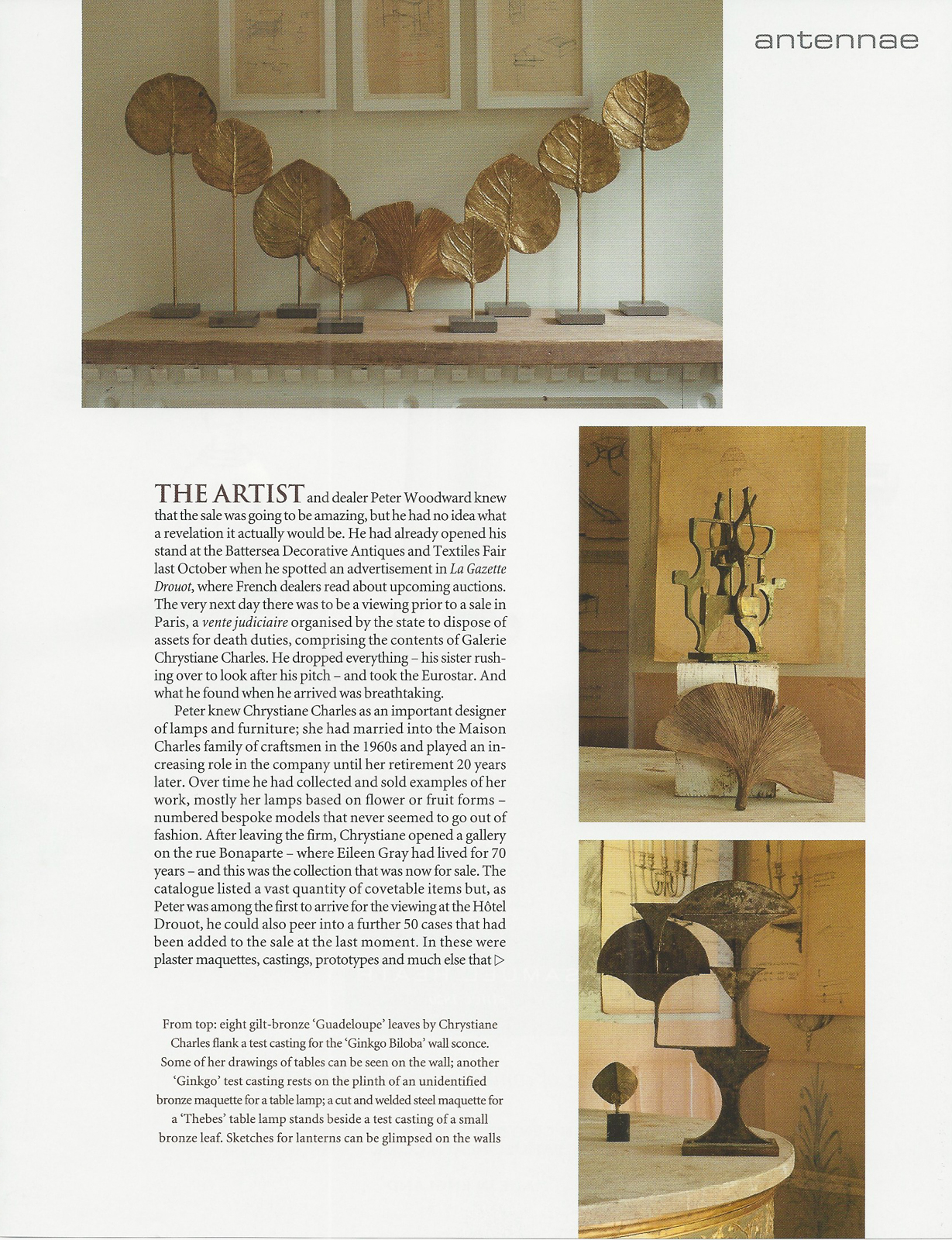

plaster maquettes, castings, prototypes and much else that

began to reveal just how significant Chrystiane had been as a

designer, and the extent of her influence in a company that

had already forged a reputation for quality and originality.

Maison Charles was a family business founded by Ernest

Charles in 1908. He began by taking over a company that

specialised in lighting and high-quality bronze casting, and

was succeeded by his eldest son, Emile Albert; Emile’s broth-

er Pierre joined in 1932. In the interwar period the firm made

high—quality Art Deco lamps and fumiture, and was known

for a time as Charles Freres. Their work was bespoke: each

piece was made to commission for private clients, decora-

tors and architects, marked with the company name and

given a model number in the catalogue.

Emile’s sons Jean and Jacques, both trained interior de-

signers, signed up to the firm in the 1950s. Then, when Jean

married Chrystiane, the style began to change: the company

launched its ‘Végétal’ range, with table lamps and sconces

based on the forms of fruits and leaves. The pineapple, pine-

cone and corncob became especially well known and sought

after. From 1971 Chrystiane became the company’s artistic

director and, eventually, its president, managing its output

until her retirement when the baton passed to a further gen-

eration, her architect son Laurent.

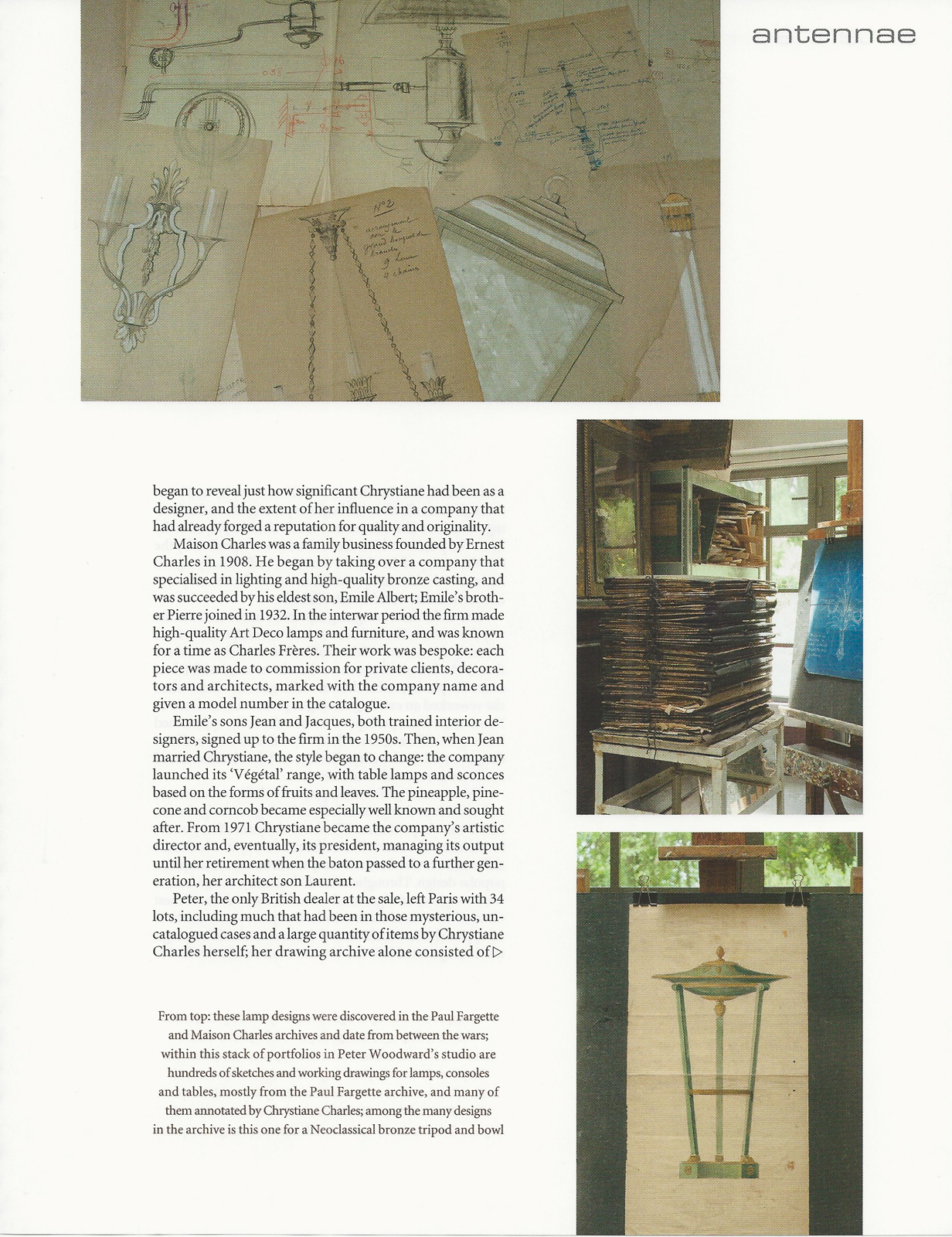

Peter, the only British dealer at the sale, left Paris with 34

lots, including much that had been in those mysterious, un-

catalogued cases and a large quantity of items by Chrystiane

Charles herself; her drawing archive alone consisted of

more than 2,000 sketches in 36 folios. Once he had been

through them all, he could begin to put together a fascinat-

ing portrait of Chrystiane and the role she had played at the

firm. The point at which she took over was signalled by the

fact that many of the objects were now individually signed

and marked with a unique number, so that their exact prov-

enance and date could be established.

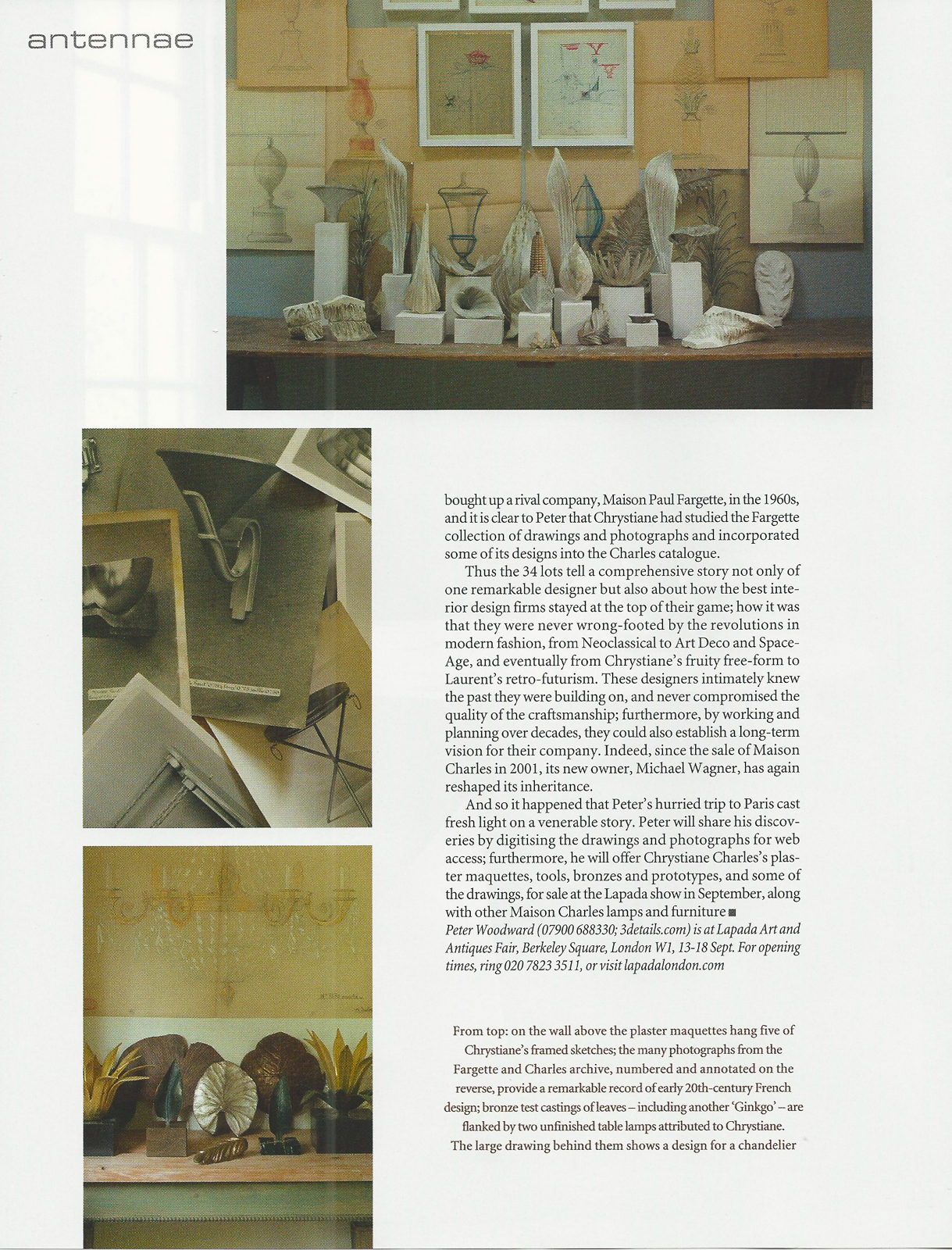

One of the most intriguing aspects he uncovered was the

way she worked. She had been trained as a sculptor, but from

the maquettes, many of them of leaf forms, Peter could see

that she built a metal armature that she covered with fabric

soaked in plaster, rather than modelling in clay. Thus, when

she reworked an existing catalogue piece — an Art Deco or

Neoclassical form, perhaps – for a new client, she approached

it in a quite different, more fluid way. Peter also learned how

designs could reach a chrysalis stage and then be abandoned

as Chrystiane moved on to a new idea.

This reworking of classical pieces for different customers

and as fashions change is the hallmark of a great design house,

and is what kept Maison Charles at the peak of its powers

for decades: the secret lies in the subtle way in which new

skills and a revived artistic temperament can reinterpret a

popular design. Throughout the 20th century, design houses

were bought or amalgamated — after all, that was how Ernest

Charles had created the firm in the first place – and each time

it happened, a new archive, and thus a new artistic language,

was incorporated into the oeuvre. Maison Charles had

bought up a rival company, Maison Paul Fargette, in the 1960’s,

and it is clear to Peter that Chrystiane had studied the Fargette

collection of drawings and photographs and incorporated

some of its designs into the Charles catalogue.

Thus the 34 lots tell a comprehensive story not only of

one remarkable designer but also about how the best inte-

rior design firms stayed at the top of their game; how it was

that they were never wrong-footed by the revolutions in

modern fashion, from Neoclassical to Art Deco and Space-

Age, and eventually from Chrystiane’s fruity free-form to

Laurent’s retro-futurism. These designers intimately knew

the past they were building on, and never compromised the

quality of the craftsmanship; furthermore, by working and

planning over decades, they could also establish a long-term

vision for their company. Indeed, since the sale of Maison

Charles in 2001, its new owner, Michael Wagner, has again

reshaped its inheritance.

And so it happened that Peter’s hurried trip to Paris cast

fresh light on a venerable story. Peter will share his discov-

eries by digitising the drawings and photographs for web

access; furthermore, he will offer Chrystiane Charles’s plas-

ter maquettes, tools, bronzes and prototypes, and some of

the drawings, for sale at the Lapada show in September, along

with other Maison Charles lamps and furniture .

Peter Woodward (07900 688330; 3details.com) is at Lapada Art and

Antiques Fair, Berkeley Square, London W1, 13-18 Sept. For opening

times, ring 020 7823 3511, or visit lapadalondon.com

read more about Maison Charles here